In 1919, Raymond Orteig offered $25,000 to the first person who would fly from New York City to Paris in one flight, in either direction.

The prize was valid for 5 years, and the Aero Club of America accepted the challenge.

Orteig extended the challenge by another 5 years when no one had been able to do a nonstop transatlantic flight by the mid-1920s.

Two French veterans were the first pair to be serious contenders for the prize.

They used a Poletz biplane with a removable wheeled undercarriage that was supposed to drop off after take-off.

Related Article – 14 Taxiway Markings, Signs, and Lights Explained By An Actual Pilot

The two pilots were planning to land on skids.

However, the plane crashed, and the pilots barely escaped with their lives.

In America, Air Service Reserve Captain Homer Berry began building a plane that could make a non-stop transatlantic flight.

Igor Sikorsky, a Russian immigrant, helped Berry in the construction of the plane.

The S-35 they designed had a wingspan of 101 feet, or 31 meters. Fully fueled, it weighed 9 tons.

French pilot Rene Fonck, a war hero, was selected to fly the plane.

Fonck insisted on several redesigns of the plane, and when he was ready for take-off on September 21, 1926, the plane was more than 10,000 pounds, or 4,540 kg, over specification.

During take-off, a wheel came loose, and the plane’s mechanic decided to release the entire landing gear to avoid a roll-over.

The S-35 disappeared behind a hill, and then exploded.

Fonck and another crewman miraculously survived the crash.

Fonck, Berry, and Sikorsky blamed each other, but the crash was ultimately ruled an “unfortunate accident.”

Surprisingly, the men decided to build another plane together and try to win the prize again in 1927.

While the trio prepared for their next attempt, another group tried their luck.

It consisted of Richard Byrd, the first to successfully fly over the North Pole; Bernt Balchen from Norway; Floyd Bennett; and George Noville.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

The Fokker Trimotor they built for their transatlantic flight flipped over during a test run in New Jersey.

Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster commissioned a tri-motor plane from the Keystone Aircraft Corporation.

During trial flights in Virginia, in 1927, the plane lost power and crashed.

Both Davis and Wooster died in the accident.

At the same time, in France, Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli began building a plane that could handle the long flight across the ocean.

Their PL-8 had a detachable undercarriage and was meant to land on its fuselage in New York Harbor.

Weather conditions were poor when Nungesser and Coli took off from Normandy.

The two men and their plane were never seen again once they left the French coast behind.

Even after Charles Lindbergh’s successful flight from New York to Paris in May 1927—for which he received the Orteig Prize—many more pilots died during their attempts to cross the Atlantic.

In August 1927, Leslie Hamilton and Fred Minchin took off from England to fly to Canada in a single-engine Fokker.

They disappeared in the fog off Newfoundland and were never seen again.

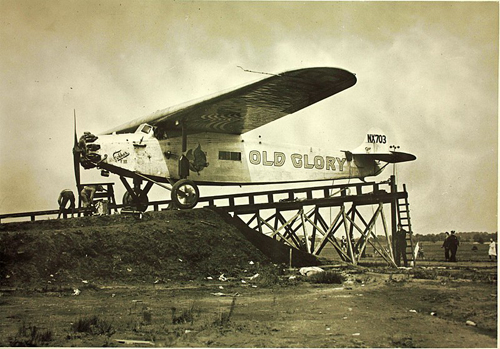

In September 1927, Lloyd Bertaud, James Hill, and Philip Payne took off from Maine to fly to Rome, in a Fokker single-engine plane sponsored by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

The plane went down off the coast of Newfoundland.

Related Article – Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC): 4 Things You Need To Know

Although the plane was found, there was no sign of the people onboard.

Only days later, a British crew of two disappeared without a trace over the ocean.

In response, the U.S. State Department and U.S. Navy called off any further attempts at transatlantic flights.