The Wright brothers are generally credited with developing the airplane, but helicopters have a much longer and troubled history.

Engineers, inventors, and scientists around the world worked to turn the idea of the “gyroplane” into a working machine.

But they lacked the necessary knowledge to control the aeronautical forces that lifted a helicopter off the ground.

Men like Jacques Bréguet, Igor Sikorsky, and Juan de la Cierva had to find a way to direct the downward thrust of the rotor blades so that it would move the machine into the air and at the same time overcome the torque created by the blades’ rotation.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

At the beginning of the 1930s, Jacques Bréguet founded the Syndicate for Gyroplane Studies and recruited Rene Dorand, a young engineer.

Together, they developed a helicopter that was much more stable and easier to control than previous models—including ones that Bréguet had built a decade earlier.

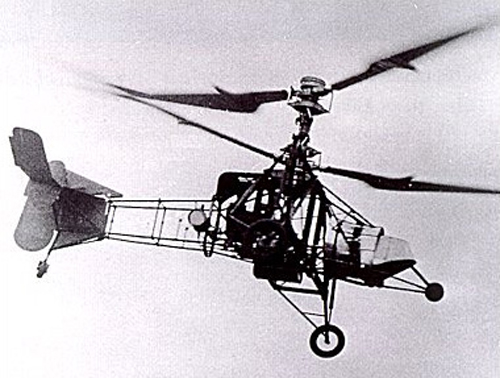

To save money, the two men salvaged as many parts as possible.

They used an airplane fuselage for the helicopter’s body, with a thin metal frame, a tail, and three wheels.

The engine, a spare airplane one, was towards the front, and behind it was an open cage for the pilot.

Twin rotor blades, spinning in opposite directions, were stacked so that their torque would cancel each other.

The pilot could control the pitch of the rotor and thus the angle of the blades.

The more they were angled, the more the lift would increase, and the machine would rise up.

In November 1933, the Gyroplane-Laboratoire, as Bréguet called his helicopter, was ready for testing.

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

But as soon as the test pilot started the engine, the machine tilted and the blades hit the ground and shattered.

Nobody was injured, but further testing was impossible.

For the next 2 years, Bréguet worked to improve his machine.

He focused on the controls in particular, trying to make it easier to control the direction of flight.

He modified the rotor axle, the rotor disk, and the rotors themselves, so that they each had a different pitch.

This allowed the pilot to steer the craft forward, backwards, and to the right and left.

On June 26, 1935, the Gyroplane-Laboratoire was ready for another test.

This time, the pilot was able to lift into the air and perform several flights at speeds up to 30 miles, or 48 kilometers, per hour.

In response to the successful flights, the French Air Ministry offered Bréguet a million francs if he could reach certain performance goals.

Bréguet continued to work on his helicopter.

He was eventually able to get it to a speed of 75 miles, or 121 kilometer, per hour and to a record height of 518 feet, or 158 meters.

His helicopter could hover in one spot for 10 minutes and remain in the air for over 1 hour.

By late 1936, Bréguet received the million-franc bonus.

Despite his success, Bréguet was unable to solve the problem of what would happen if the engine failed.

Unlike an airplane, which could glide to the ground if the engine stopped working, a helicopter used its rotors almost like a parachute when descending. Without working rotors, the helicopter would crash to the ground.

With World War II eminent, Bréguet was unable to work on this problem.

He focused on bomber production instead.

Related Article – 14 Taxiway Markings, Signs, and Lights Explained By An Actual Pilot

Although the Gyroplane-Laboratoire had its problems, many aviation experts consider it to be the first successful helicopter.