The mechanics that make helicopter flight possible have been around for centuries.

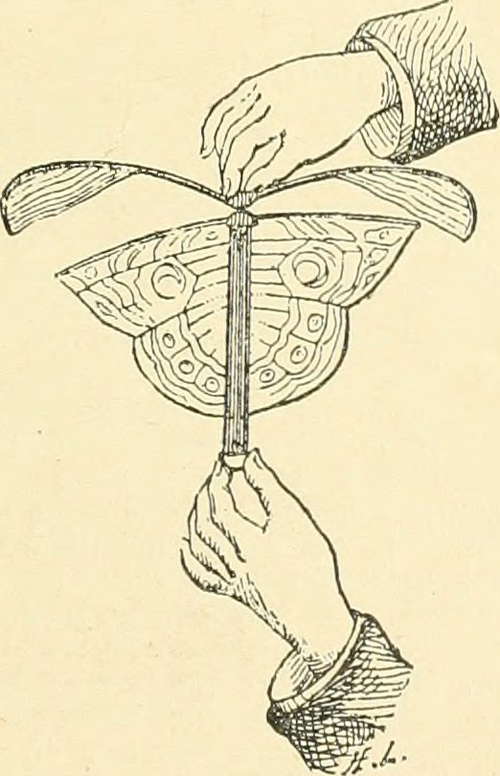

In ancient China, children put slightly twisted feathers on sticks and rapidly spin them, so that they would lift into the air and gently fly back to the ground.

In ancient Greece, the mathematician and inventor Archimedes created a rotating screw for a water pump that used the same mechanics a helicopter uses to lift off.

Related Article – 14 Taxiway Markings, Signs, and Lights Explained By An Actual Pilot

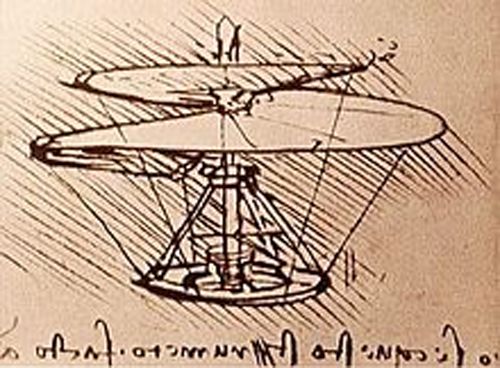

And in medieval Italy, Leonardo da Vinci built an “air gyroscope” with iron wire and linen that became the first “helicopter” theoretically capable of lifting a person into the air.

A number of inventors after da Vinci created rotary-wing aircraft, but they were all too heavy to stay in the air for long, and they all lacked the power to overcome the torque of the propeller.

It wasn’t until Mikhail Lomonosov built a coaxial rotor machine that vertical flight became a real possibility. In 1754, Lomonosov used the Chinese top as a model, but added a wound-up spring that enabled his device to climb and fly freely.

In 1783, Christian de Launoy, a French naturalist, expanded on the Chinese top model to create a flying machine. He used two sets of counter-rotating turkey feathers to achieve lift, since the forces of the sets moved into opposite directions and thus canceled each other.

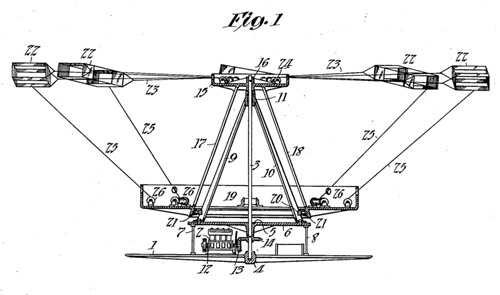

In Great Britain, George Cayley designed a double-rotor helicopter in 1792. He used clock springs and tin in his models, but the steam engines available at the time were too heavy to actually lift his “aerial carriages” into the air.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

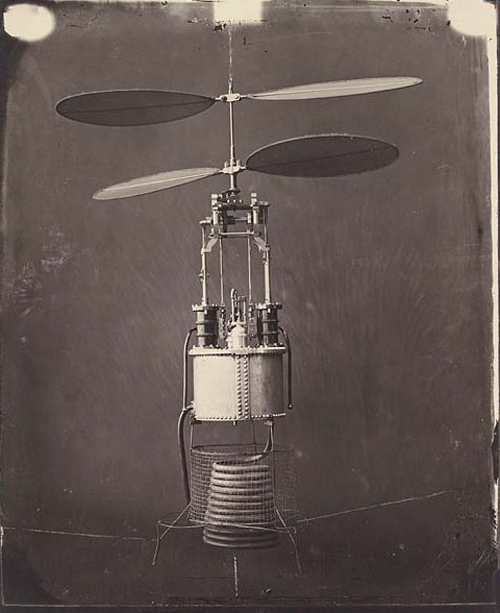

Cayley’s fellow Englishman W. H. Phillips was the first to successfully use a steam engine to lift a vertical flight machine off the ground. He built a tiny boiler that blew steam out of its blade tips to power his machine. It was the first time that a helicopter was powered by anything other than the stored energy found in such devices as a wound-up spring.

During the Civil War, in 1862, William Powers constructed a helicopter based on Archimedes’ early designs. It used a steam engine to propel the machine upwards and forward. Powers intended to use it to break through the Union Army’s siege of the South, but he never built a full-scale machine.

In France, an association with the single goal to advance helicopter designs was highly successful. In 1863, the Vicomte Gustave Ponton d’Amecourt built several machines with counter-rotating propellers. He used spring propulsion for his models, which were some of the most successful machines to date.

In 1870, Alphonse Penaud used the Chinese top as inspiration for his models. He used rubber bands to move two screws that rotating in opposite directions. Some of his helicopters flew as high as 50 feet, or 15 meters, into the air.

Unsurprisingly, American inventor Thomas Edison took a great interest in these vertical flying machines. He experimented first with an early form of the internal combustion engine—which blew up his laboratory—and then with an electric motor.

Edison realized that both an aerodynamic rotor and a powerful engine were needed to achieve hovering efficiency and long flight times.

It wasn’t until the internal combustion engine had become widely available that helicopter inventors were able to overcome the technical challenges that vertical flight presented.

Related Article – Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC): 4 Things You Need To Know

Together with the engine and a growing understanding of aerodynamics, inventors were able to finally overcome the challenges of excessive vibrations, lack of stability and control, and weight that had plagued early developers.