In France, Jacques Schneider was one of the people who pushed for advances in aviation.

He argued that planes should be able to land on both water and land because many large cities are located close to large bodies of water.

To encourage experiments with seaplanes and flying boats, Schneider created an international competition in 1912.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

In addition to a trophy, winners of the competition would also receive a £1,000 prize.

In order to be eligible for the Schneider Cup competition, a plane had to come into contact with water twice during its flight.

It had to be able to float for six hours and travel at least 550 yards, or 503 meters, on water.

If a seaplane, or pontoon, took on water while floating, it then had to fly with this added weight.

Schneider decreed that the winner’s home country would host the competition the following year.

The Schneider Cup would be awarded permanently to the country whose pilots won three times in a row.

In 1913 and 1914, the race Schneider had envisioned was held off the coast of Monaco.

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

In both years, participating planes were traditional land planes that had hastily been equipped with pontoons.

Maurice Prevost won the first Schneider Cup race in 1913.

He flew a Deperdussin with pontoons attached to the bottom of its fuselage.

The pontoons had taken on a lot of water during the water portion of the race, and Prevost barely made it across the finish line.

However, he was the only pilot to finish at all.

In 1914, the British pilot Howard Pixton won the race.

He fulfilled the race’s stipulation that the plane had to “come into contact with water” by bouncing it across the surface, rather than actually landing it on water.

This maneuver gave Pixton the advantage, and he was able to finish the race in half the time it had taken Prevost the previous year.

The race was suspended during World War I. In 1919, it was resumed near the Isle of Wight off the English coast.

Only one pilot finished the race, Guido Janello from Italy, and he was disqualified for taking the wrong course.

In 1920 and 1921, the race was held in Italy, and the home team won both years.

The next year, France and England put up several teams each, determined to prevent Italy from winning for a third straight year and keeping the Schneider Cup permanently.

The race was close.

Related Article – 14 Taxiway Markings, Signs, and Lights Explained By An Actual Pilot

The winner was the English pilot Henri Biard, whose incredible flying skills made up for the inferiority of his plane.

Seaplanes required more powerful engines to take off, but the longer distances available for takeoff on water also allowed builders to design planes with smaller wings.

With less drag and stronger engines, the planes built for the Schneider races often set speed records.

In 1914, the average speed of the race was 86 miles, or 138.5 kilometers, per hour.

In 1922, the average speed had increased to 146 miles, or 235 kilometers, per hour.

By 1923, the Americans, supported by the U.S. Army and Navy, were strong contenders in the race.

Lieutenant David Rittenhouse won the race that year in a Curtiss CR-3.

One reason for his win were several improvements to the plane he was flying.

The newly developed CD-12 engine had a built-in cooling system that allowed coolant to flow directly into the sleeves where heat was generated.

This new wetsleeve-monobloc engine took up less space than previous engines, which allowed for a sleek plane design.

As a result, Rittenhouse won the race with a record average speed of 177 miles, or 285 kilometers, per hour.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

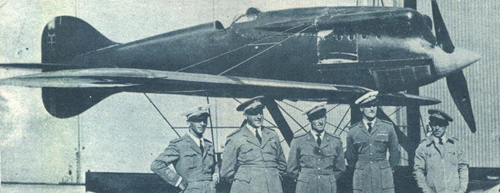

England was the first country to win three consecutive races, in 1927, 1929, and 1931.

This meant the Schneider Cup came into the country’s permanent possession.

In each of these races, the winner flew a Supermarine plane equipped with a Rolls-Royce engine.

Jacques Schneider died in 1928, but it is universally acknowledged that his Schneider Cup competition was responsible for incredible advances in aviation research.